I cannot even tell you how many times I have been to the Buffalo Museum of Science. As a young girl, we frequented there approximately once a month on Sundays as part of our family day together. I loved it. I can remember the endangered species exhibit where stand next to a life-size rhino replica. I remember the traveling exhibit of animatronic dinosaurs. My favorite though was the dioramas. Capturing a moment in time, you could look into the secret world of animals as an unobtrusive observer for as long as you wanted.

I’m now a full-blown scientist with a doctorate, but it wasn’t until recently that I fully understood what museums were all about. At the University of Missouri, where I did my dissertation research, I was friends with a postdoc who was always looking for dead birds and mammals to skin as specimens. He was in charge of the university’s museum. I didn’t think much of it at the time except that I thought he just found the prep part itself interesting.

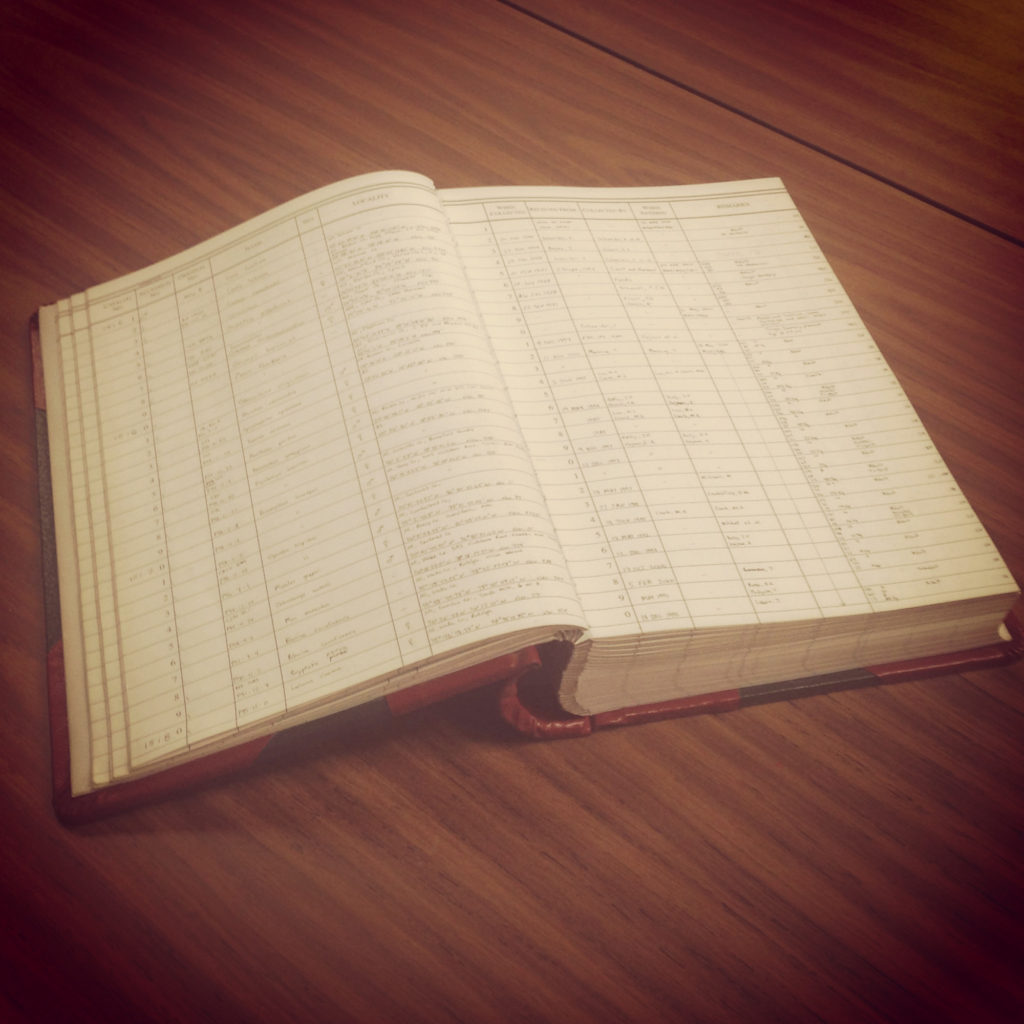

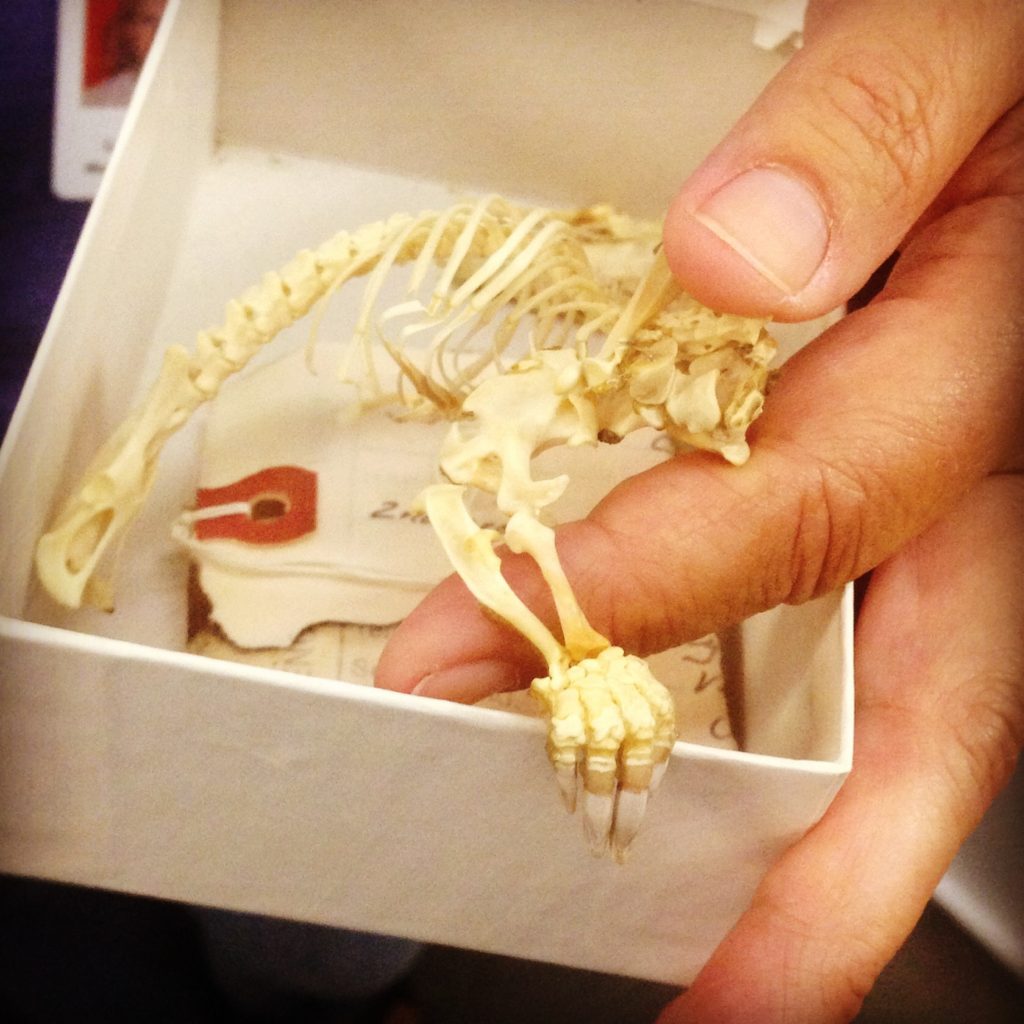

You can’t see the museum from the outside. It is largely contained in one classroom and all you can see are large file cabinets. Inside these cabinets were trays of hundreds of animals arranged by their taxonomic status. The animals aren’t stuffed into poses like those in dioramas, but are laid out for research. It wasn’t until I became in charge of the museum during my postdoc work that I really understood the value of the museum and what it was.

Scientists come to the museum or the museum loans out specimens for research purposes. These specimens allow scientists to look into the past to compare to species living today. Some of the questions researchers might pursue include those understanding the relationships between taxa including species designations. For example, the olinguito was recently discovered through examining museum collection specimens. When diseases break out, such as the aggressive and virulent Devil Facial Tumor Disease, a cancer that is decimating Tasmanian devil populations, scientists can go back to museum specimens to look for clues to aid in combatting it. Specimens also provide important sources of DNA. Although controversial, scientists would use museum specimens like Martha, the last passenger pigeon, to potentially revive the species and bring it back to life.

I recently was fortunate to visit the mammal collection at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, which is about 100 times larger than the museum at the University of Missouri. Below are some of the interesting findings you would not know about…

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

Love this post? Share it with friends!