Scientific papers (AKA publications) are extremely important for your career as a wildlife biologist or scientist! If you did an experiment or researched something, but never shared the outcome, what would be the point?

If you remember the scientific method that you learned in middle school, the scientific paper represents the last step: communication. Publishing peer-reviewed manuscripts (a manuscript is the draft of your paper) is the most important way in which scientists communicate with one another.

Science by definition builds off of previous knowledge and this knowledge is shared in peer-reviewed journals, or what we collectively call the literature.

Publications are not only vital for progressing science, but will likely help your career too. For many jobs, you need a publication record. Typically, the more publications you have, the more competitive you are for a job, but employers also look at things like the quality of journals that you publish in and whether you are a first author or not (more on that next week).

I just started writing a new paper myself this year, so I thought this was the perfect time for me to write about how to write a paper (how meta!). But first…

What is a Scientific Paper?

A scientific paper is a write up of a study that is published in a peer-reviewed journal. They typically include the following sections:

- Introduction: Sets up the scientific question or objectives of the study

- Methods: Explains what you did for the study

- Results: Your results objectively stated

- Discussion: Interpretation of what your results mean in light of other published studies

Statements throughout the manuscript will have to be supported and cited by previously published studies so it makes sense in light of what has been done before. You will have a references section with all of them listed.

You can check out scientific papers for yourself. There are a lot of free PDFs on Google Scholar (some are behind paywalls) and journals like PLoS and PeerJ are open access. You can check out mine here (if you click on a paper, it will take you to a PDF if there is one).

How Does a Scientific Paper Get Published?

After you are finished writing your paper and formatting it for a specific journal, you go to that journal’s website and upload it for submission. The paper may be rejected right away, or sent out to experts in the field to review. (Don’t be discouraged if you are rejected right away! It happens to all of us. Read these tips to help recover and submit to another journal).

These experts will read your manuscript and critique it, and suggest a decision: minor revisions, major revisions, or rejection. By far, most often it is the latter two.

If you are given the option to revise (major or minor revisions), you then have to list each of the reviewer’s critiques line-by-line and either agree with them and change your manuscript to reflect this, or dispute them and explain why (read this post for tips on how to do this).

The manuscript and your responses are then sent back to the editor and reviewers. They again are given a chance to read all of your explanations and decide if it is ready to be accepted. Sometimes your manuscript will go through 2-3 rounds of review by usually the same reviewers, but sometimes new ones. Once a manuscript is accepted, it is then published by the journal for other scientists to read.

The peer-review process is a way to ensure that the research you are conducting is valid and your interpretation of the results are appropriate. If other scientists find your results bogus, they have the entire method that they can then replicate and try for themselves, and/or they can also write a paper in response. Once published, scientists will use your paper to help them better understand the field and drive future studies.

Who Peer Reviews Your Scientific Paper?

Other scientists! These include other professors, graduate students, or professionals in the government, nonprofits, and other places. You start getting asked to review papers once you publish a paper yourself and most people who review have graduate degrees.

If you are a graduate student and want experience reviewing papers, you can ask your advisor if you can review one of theirs. Advisors are often sent too many to review and are looking for someone to recommend to the editor to pass their paper off to.

When Should You Start Writing a Scientific Paper?

Right away if you are leading a study (the first author). I highly recommend you start your writing when you are collecting data. I am really bad at doing this (do as I say, not as I do!). If you write your methods as you are actually doing them during the data collection process, everything will be fresh and you will thank yourself later when you go to start the rest of your paper and realize you are already done with your methods.

How I Write My Scientific Papers: 10 Steps

I kind of do steps 1-6 all at the same time. As mentioned before, it’s best to write the methods first, but I also work on the data analysis and introduction parts depending on my mood while collecting and analyzing data. Here I will show you how I approach writing a paper using the one I am working on now as an example.

1. After or while I am writing my methods, I usually start with my big question. When writing my introduction, I start first by getting clear on what I am writing about. To do this, I condensing my entire paper into one research question. Example:

Research question: Does eMammal citizen science improve children’s perceptions of local wildlife?

eMammal is the citizen science camera trapping program that I work on. We conducted surveys of students’ attitudes towards wildlife before and after they participated in eMammal at their schools.

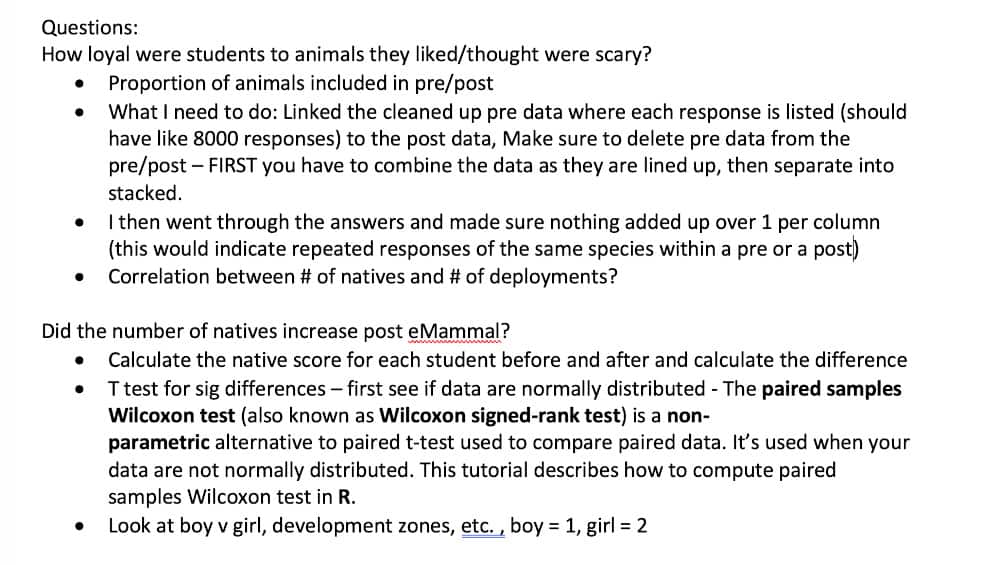

2. Then I copy my question and paste it in the methods section. You probably already wrote the methods for the data collection portion, but you will need a separate data analysis section within the methods.

In this data analysis section within the methods, I break my question down into smaller questions that help guide my analyses. Then under each part, I bullet the types of analyses that I need to do. Here’s an example:

Don’t worry about grammar, writing in complete sentences, formatting, etc. You will see that for some of the statistics I did, I copied and pasted text right out of a website I used to I can perfectly define the analysis and why I chose it.

3. I then copy and paste those questions into my results section. As I am doing my data analysis, I write the results in very simple, often incomplete sentences. I write them under the questions that I am answering that I just copied and pasted from the methods analysis part.

4. You can work on the introduction at any time. I personally like to write the introduction first because it helps me (1) wrap my brain around what the story of the manuscript will look like, and (2) write with an unbiased perception/vision since I don’t know what the result will be yet.

The introduction sets the stage for the question and at this point the reader does not know the answer. If I get too far into the results and know the outcome already, I feel like this puts a bias in the way that I write. Some people like to know the results first, so they can figure out the “story” of their data and write the introduction to set up the story.

You may yourself approach different papers differently when you begin to write them. I am dealing with a really large survey data set, so I may find some really interesting outcomes that are separate from the main study question I was asking. In this case, I might write a second paper and flush out the analysis first to then go and write my introduction.

As you write the introduction, think about what journal you want to submit your paper for. Think about this well in advance so your tone and word count matches the expectations of the journal (Check out this post for how to choose a journal).

5. When writing my introduction, I go back to my one general research question. Then I ask myself how is this question different from anything that has been done before? Here’s an example with the paper I am working on now:

Does eMammal citizen science improve children’s perceptions of local wildlife?

- No direct conservation or educational messages about specific animals, instead it’s a citizen science approach – is this enough to change perceptions?

- Data collection for use in real scientific studies (as opposed to educational programming)

- No research on this in children

I then use these to identify the main components of my introduction which are: citizen science, children, and perceptions of wildlife.

After I have my main components, I start to outline my paragraphs. There will be an intro paragraph, a paragraph for each component, and a closing paragraph. Your introduction will go from broad concepts to the specifics of which your paper will address (think of an upside-down triangle).

- First paragraph: Intro. Extremely broad sentence to bring things into context about what you are going to discuss (e.g. We are in a biodiversity crisis. We can’t save everything. How do scientists decide what to save?)

- Second paragraph(s): Wildlife perceptions (first component). Importance: Can make or break conservation efforts. (e.g. For conservation to work, we need to make sure the public cares about what scientists think is important). How does public prioritize species over conservation?

- Third paragraph: Children (second component). They are the future stakeholders. Malleable values, more open to information than adults. Experiences that happen when you are young last a lifetime. We know little about children’s attitudes towards animals.

- Fourth paragraph: Citizen science (third component). Inquiry-driven. Purposeful: answers real questions scientists have. Ownership and pride in data collection. Exposure educational programs work, but more difficult to align them to school standards.

- Fifth paragraph: Bringing them all together again to lead to your question/objectives.

Some may take more than one paragraph, but not too many, otherwise your introduction gets long.

6. Now that I have the outline, I start writing sentences. DON’T WORRY ABOUT QUALITY AT ALL. Just get words on the paper. Words on the paper will give you something to work with, otherwise you will just be staring at the screen forever. Later you will go back to those words and try to make them into more well-constructed sentences.

If this is a new research topic to me and I do not know the literature well, I copy and paste sentences directly from papers that I am reading that will be helpful for me in writing a new sentence. When I do this, I HIGHLIGHT the entire copied section in a special color so I know they are not my own words and afterwards write briefly where they are from (e.g. Schuttler et al. 2015 J of Zoology). Then when I start to write, I write the sentence in my own words and delete the one that I copied and pasted.

7. After analysis is finished, I think about what figures I want to put in my paper. I know other people do this backwards; they do all analyses first decide and then decide what figures tell the story, but I find it more helpful to think about my figures after I write the introduction so I know what will be important to show.

You do not need to put everything in. Put in key figures that are important in telling the story. This takes practice to know what is important and not. Keep reading lots of papers to help you!

8. I then rewrite my results in full statements. I find the results section hard to write because it has to be objective (no interpretation of results), but you do have to write it in a way that allows people to start making sense of the results. This is hard to explain and takes practice. You don’t want to just repeat everything that can be summarized in a table, but you don’t want to interpret.

9. Write your discussion. Discussions are the hardest to write in my opinion. It’s kind of like working backwards from your introduction. Your discussion mirror your introduction. In fact, I find it helpful to copy and paste the first sentence or key sentence from each paragraph of the intro to help me write the intro.

In the discussion, you will discuss your results in the context of what has already been published. Are they what you expected? Do they contradict or support the literature? What do they mean for future studies.

I haven’t finished analyzing my data yet, but here are some things that I will likely include in my discussion.

- First paragraph: Summary paragraph about your results and key findings. Here you add interpretation (e.g. Surprisingly, we found…)

- Second paragraph: Wildlife perceptions (first component). Were wildlife perceptions changed? Which ones were or weren’t? To what magnitude?

- Third paragraph: Children (second component). What were the results from the children? What we expected? Are they different from what is published about adults? Did all children have the same response?

- Fourth paragraph: Citizen science (third component). What were the results from citizen science only approach. What we expected? Are they different from what is published about educational programming with a specific agenda? What is different about citizen science and how may have this influenced results?

- Fifth paragraph: Another summary, but different from the first. This summary is more global. It is a more conclusive paragraph about what your study means for science and future studies.

You will probably need more than just these five paragraphs to explain some surprising things you found and your paragraphs may not necessarily follow this same order as the introduction to make them flow.

When reviewing other people’s papers or helping students, the most common mistake I see with discussions is that they do not discuss their results enough. This is not just a recap of the results section. You need to bring in other studies that have been published before and explain how your results were similar or different and what it means for science.

10. The final step of writing and probably something you want to think about while you are writing is the journal’s author guidelines. These are specific rules you have to follow to submit such as word count, reference style, etc. Some journals are really specific so make time for it. It’s a pain in the ass though! You also have to add acknowledgements, keywords, etc. Your journal will tell you everything you need to include.

Additional Things You May Not Know About Writing a Scientific Paper

It Usually Costs Money to Publish

Yep! Someone interested in publishing on their own messaged me on Instagram saying they were shocked by this. My papers cost between $900 to $3500 to publish. You should not have to pay for this yourself unless you are a principal investigator. When you write grants as a professional investigator, make sure to include money for publications!

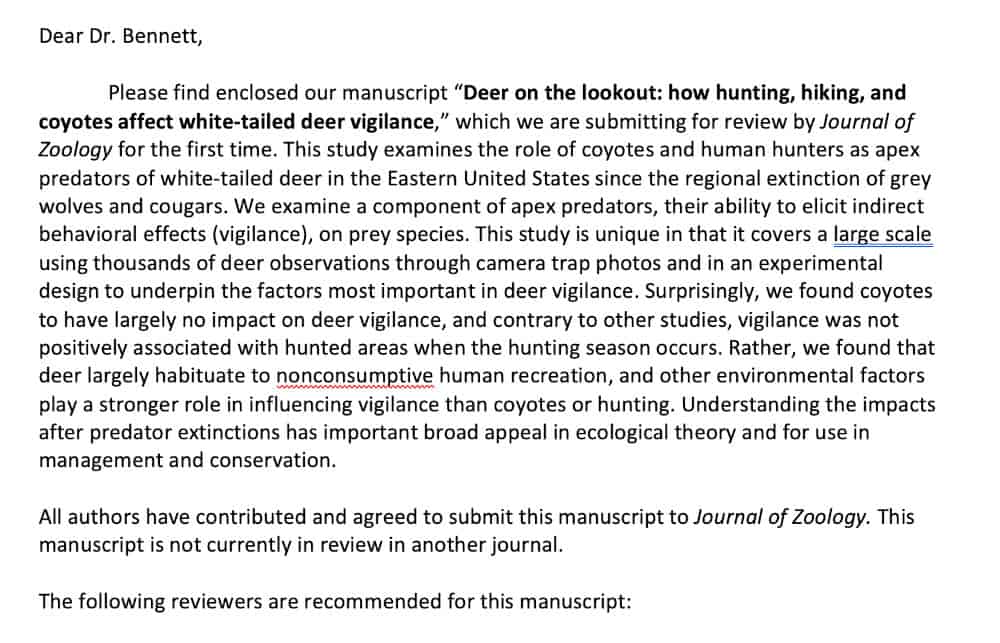

Prepare a Cover Letter and Have Potential Reviewers in Mind

You may think you are finished once you are done writing, but you still need to write a cover letter explaining why you think your study is a great fit for the journal and the impact it will have.

You will also need to provide the names of 3-5 scientists that would be appropriate to review this paper. Who is appropriate? Scientists that have expertise in the topic you are writing about. Unfortunately not your friends.

Allow 1-2 Hours to Submit a Scientific Paper to the Journal

Submitting a manuscript is not like sending a file via Dropbox. For most journals, you have to enter each author, their institution, and contact information manually and separately in pages within a website.

They also usually ask you to copy and paste your abstract, title, keywords, etc. It can take a LONG time. If it’s your first time, allow yourself at least two hours to upload. Again, a pain in the ass. But it’s super gratifying when you are done!

There you go! There are my tips. I hope this helped you out, but please take them with a grain of salt and ask others for advice. Not everyone writes papers the same way and. I don’t even follow this exact format every single time. What approach and tips do you use?

Love this post? Share it with friends!